WIDE-RANGING IN STYLE AND EXPRESSION, AN EXHIBITION IN TOKYO SHOWCASES WORKS BY ARTISTS WHO SHUN FAMILIAR LABELS

Published on August 1, 2025

by Edward M. Gómez

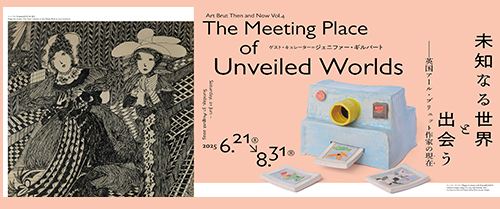

“Art Brut Then and Now Vol. 4:

The Meeting Place of Unveiled Worlds”

Tokyo Shibuyakoen-dori Gallery

June 21 through August 31, 2025

TOKYO — Tokyo-to Shibuyakoen-dori Gallery, which is located in the heart of the Japanese capital’s popular Shibuya district, is one of the most important venues in all of Japan for the presentation of paintings, drawings, mixed-media objects, and other creations conceived of and produced by self-taught artists.

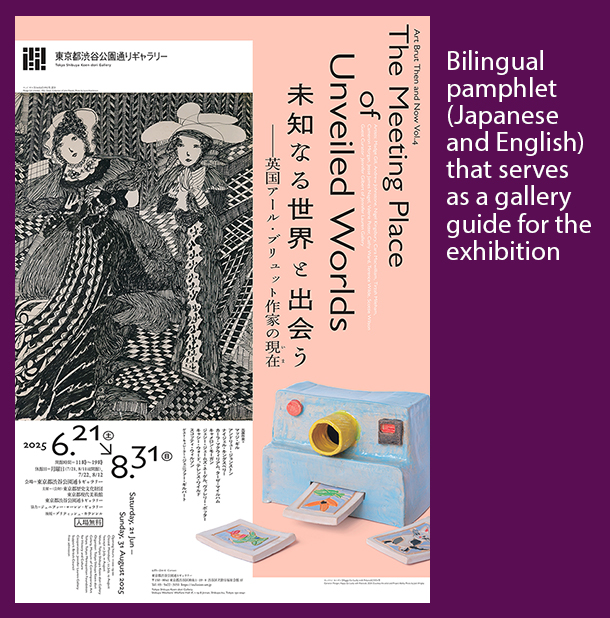

Since it opened in early 2020, this venue, which is an annex of the Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo, has also shown works created by academically trained artists. Each year, it presents several exhibitions, each of which is accompanied by an attractively designed, well-illustrated, bilingual (Japanese and English) catalogue.

(See the bilingual, Japanese-and-English pamphlet for the exhibition here. A .pdf file will open.)

Now, Tokyo-to Shibuyakoen-dori Gallery is presenting “Art Brut Then and Now Vol. 4: The Meeting Place of Unveiled Worlds,” an exhibition of works in a variety of materials and genres made by eleven British artists, eight of whom are living and working in the United Kingdom today. Three of them are deceased.

All of the artists whose works are featured in “The Meeting Place of Unveiled Worlds” have created distinctive art forms that have expanded, in technically innovative and visionary ways, the meaning and broader language of the related genres that are known as “art brut” and “outsider art.”

However, as Jennifer Gilbert, a young British art dealer who served as the exhibition’s guest curator, explained at its grand opening a few weeks ago, she prefers not to assign any familiar category labels to the works on view or to their creators. Similarly, the exhibition’s participating artists themselves shun identifying labels that can be too limiting or simply inaccurate, given that each of them has a unique life story and deeply personal reasons for making his or her art. Thus, Gilbert said, no one label can adequately encapsulate the range of artistic outlooks and art-making motivations the exhibition reflects.

In the U.K., Gilbert has long worked with self-taught artists who have been affected with various kinds of disabilities. About a decade ago, at Pallant House Gallery, a museum known for its collections of British modern art, she helped oversee a program that brought together works produced by self-taught artists throughout Britain and then sent them out to various cities in the form of professionally curated exhibitions. (Pallant House Gallery is located in the city of Chichester, near the West Sussex coast, about 80 miles, or 130 kilometers, southwest of London.)

After moving on from that role, in 2017, Gilbert established her own gallery, whose exhibitions and related programs focus on the promotion of works made by what she describes as “disabled, neurodivergent, and self-taught artists.” From her base in Manchester, in the north of England, she organizes and stages exhibitions and other events at venues in London and other cities. Gilbert, who earned a master’s degree in the field of art, health, and well-being, has served as a consultant to museums and organizations that are interested in increasing the access of disabled people to their programs, and her gallery has taken part in the annual Outsider Art Fair in New York.

Gilbert told members of the press and guests at the exhibition’s opening, “When I set up my gallery, I did so because I realized that noteworthy art creators who are disabled will not survive without support from people like myself. Today, my gallery works with about 20 living artists from around the world, including some artists in Japan. ”

The design of “The Meeting Place of Unveiled Worlds” was created by Shunichi Miki (art direction) and Moe Hirota of Bunkyo-Zuan-Shitsu (installation design). The exhibition’s understated color palette and its presentation of three-dimensional objects in pedestal cases or in specially constructed wall niches (for Cara Macwilliam’s delicate, abstract sculptures) help accentuate the physical presence of the artworks on display.

“The Meeting Place of Unveiled Worlds,” which received support from the British Council, a cultural affairs agency of the U.K. government, serves to introduce, for the first time, almost all of these artists’ works to viewers in Japan, although, in the past, examples of Gill’s and Wilson’s drawings have been seen here in other institutions’ thematic, group exhibitions.

Gilbert’s selection of artworks for the exhibition calls attention to a wide variety of deeply personal creative expressions. She said, “This show, like other exhibitions with which I’ve been involved, challenges what conventional contemporary art spaces present without necessarily emphasizing that the artists are disabled. However, when you learn something about each artist’s personal story, you can appreciate with deeper understanding what they do.”

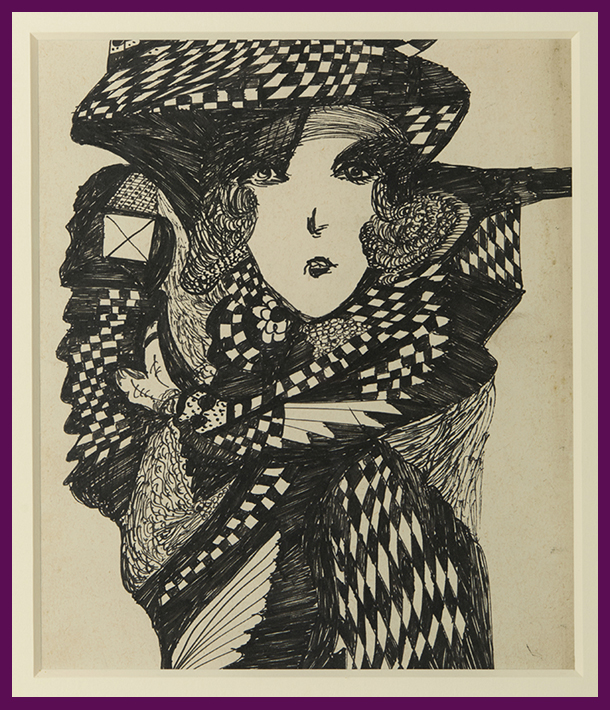

The exhibition kicks off with a group of Madge Gill’s ink or ink-and-crayon drawings on paper, whose semi-abstract compositions feature mysterious female faces that pop up and float through passages filled with cross-hatching and random patterns. Gill was in her late thirties when she began making her drawings, believing that she was guided in her art-making by a spirit she referred to as “Myrninerest.” Gill made images on cardboard, plain postcard-size paper, and fabric. Her works are regarded as emblematic examples of mediumistic art.

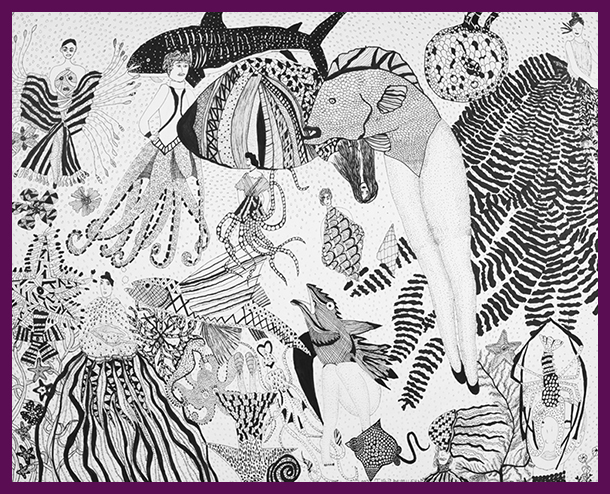

“The Meeting Place of Unveiled Worlds” includes a large drawing by Tirzah Mileham (born 1971), a former seamstress and pattern cutter who suffered a brain injury. Today, her monochromatic works, like “When Women and Fish Took Over the World” (2022), are packed with different figures — here, of course, many examples of underwater life as well as some unusual, half-fish, half-women creatures — and are executed with an eye to fine detail.

Terence Wilde (born 1963) identifies himself as a gay artist. He studied textile design and has worked as an educator, and as Gilbert pointed out, “has become a self-taught maker of ceramics who calls himself ‘an adult survivor’ of life’s hardships.” About Wilde’s compulsion to create, she observed, “If he didn’t make art, he would end up in the emergency room.”

That kind of therapeutic function of art-making, which motivates the artists whose works are on view, is one Gilbert recognizes and respects. Similarly, she acknowledges that each artist chooses to identify and categorize himself or herself — or not — according to his or her own preferred labels.

The artist Andrew Johnstone’s parents traveled from England in order to attend the exhibition’s opening. Johnstone’s mother noted that her son, who was born in 1986, “is extremely autistic and completely non-verbal.” She recalled, “At first, he was not interested in making art, but one day, he was given a pen and some paper, and he began making the most remarkable drawings.” On view in the exhibition are Johnstone’s ink-on-paper drawings of a rhinoceros and an orangutan, plus his ceramic lion figures.

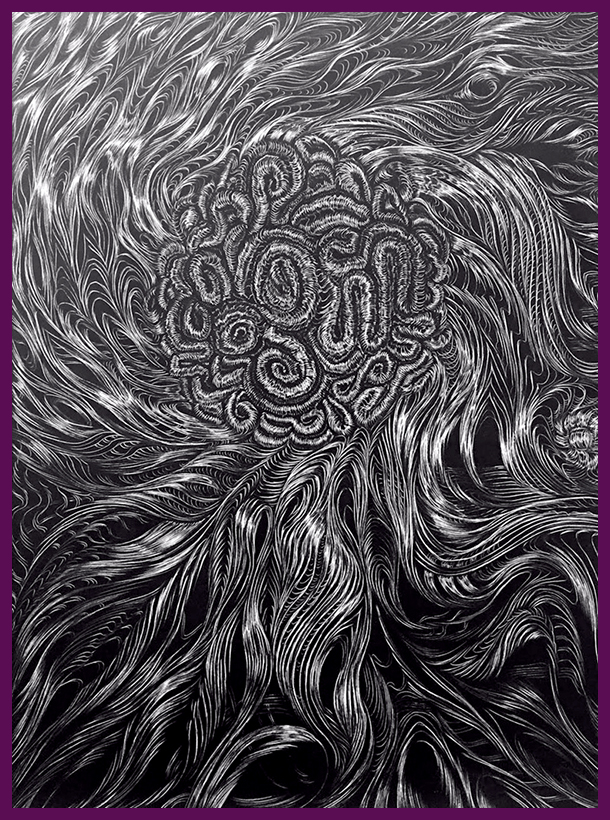

Cathy Ward (born 1960) is a London-based maker of paintings, mixed-media drawings, and sculptural works, many of which allude to the human body and to primordial or mysterious natural forces. She is interested in esoterica and the occult, and in mediumistic art.

Three of her black-and-white paintings are on view; their dense compositions swirl with rhythmic forms resembling flowing strands or neatly arranged tufts of hair. To make her smaller pictures, with their strange, smoky atmospheres, she paints thick, black ink over a thin clay surface, then etches into it with a tool to make patterned lines revealing their underlying white backgrounds. This is a technique she devised herself.

The late Nigel Kingsbury created his “delicate portraits of mystical goddesses,” as Gilbert describes them, by first drawing female nudes. Onto each figure, he then constructed a glamorous gown by applying and building up thickets of fine pencil strokes, giving his subjects and their garments illusory, fluffy grand volumes and, at the same time, an ethereal air.

In recent years, colored-pencil, abstract drawings made by the artist Cara Macwilliam (born 1972) have enjoyed great success whenever Gilbert has brought them to New York’s Outsider Art Fair.

In an interview for the London-based College of Psychic Studies’ website published in 2022, Macwilliam said, “I really loved art when I was younger but my GCSE [General Certificate of Secondary Education] art teacher knocked the confidence out of me. I stopped creating physically but stayed in love with art itself. However, in 2018, I started creating during a severe [chronic fatigue syndrome] relapse, which changed my life so dramatically that I haven’t stopped since. I can’t create every day. In fact, I can only create [from six to seven] hours per week, but the positive effect those hours have on my sense of self is priceless.”

In the current exhibition, Macwilliam’s small, hand-formed sculptures allude to her fluctuating-energy physical condition. They reflect the vulnerability of her own being in the fragility of their construction. They’re composed of stacked-up, curly chips of oven-baked, plastic modeling clay. Luminously white, they resemble fragments of strange sea shells. Delicately balanced, these sculptures could collapse at any moment.

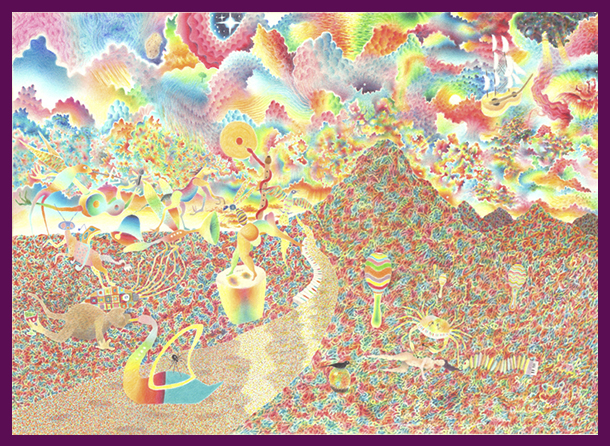

Jesse James Nagel (born 1993) makes exuberantly colored, highly detailed drawings using colored pencils on paper. Their look is surrealistic and pop, and, against the backdrop of so much imagery that, today, is generated by computers and artificial intelligence, it’s both impressive and humbling to see how vividly and with what precision Nagel gives tangible form to his visions. Gilbert said. “Jesse is affected by agoraphobia. He never leaves his house except to go out to buy cigarettes. It can take him up to six months to complete one drawing.”

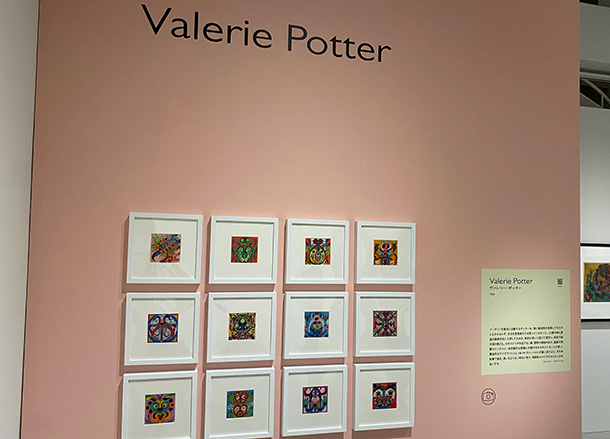

About Valerie Potter (born 1954), whose hand-stitched works on fabric employ materials and a technique that are rarely seen among the creations of better-known self-taught artists, Gilbert noted, “Valerie, who is now 71 years old, grew up in Jamaica and Nigeria before moving to the U.K. She has a wild imagination, which you can see, for example, in what look like her alien flowers from Mars. She says that, whatever idea she comes up with, it must come out in the form of her art, which she must start making that same day.”

It might be a big coincidence, but the artist Cameron Morgan’s brightly colored ceramic works, which replicate antique cameras, including an old Polaroid, perfectly capture the hip, rollicking spirit of the Shibuya district, in which “The Meeting Place of Unveiled Worlds” is being presented, with its many fashion boutiques and youth-oriented attractions. Morgan (born 1965), who comes from Scotland, told Gilbert that he was very excited that his ceramic sculptures were going to be exhibited in Japan, the world’s center of pioneering camera technology and design.

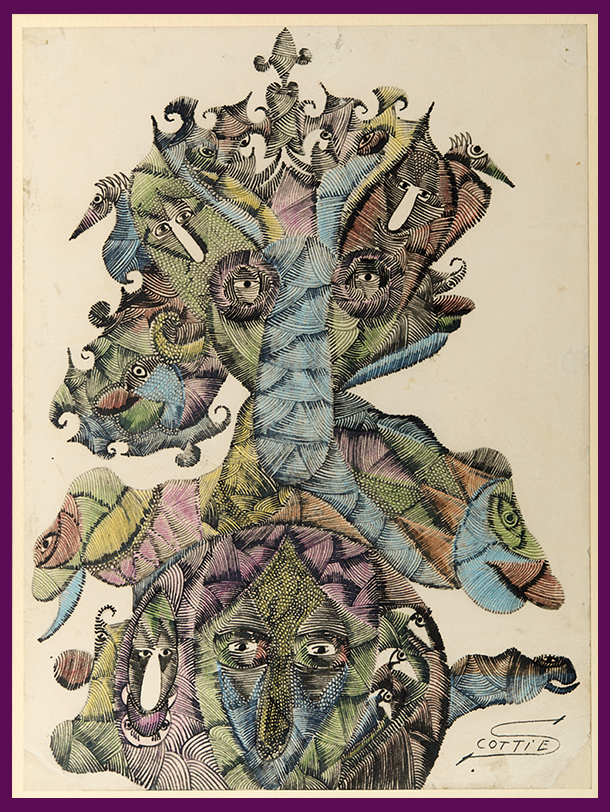

Using ballpoint-pen ink, watercolor, and crayon on paper, the Scottish artist Robert “Scottie” Wilson made colorful drawings into whose densely packed, cross-hatched passages he embedded eyes, birds, and leaf-shaped motifs. Wilson’s strange forms feel at once intimate and monumental; some of them seem to possess a kind of architectural sturdiness that feels sculptural. The artist moved to Canada in 1931 and, shortly thereafter, began making art. After he relocated to London in 1945, his work attracted the attention and admiration of the Surrealists.

At the exhibition’s opening, Gilbert explained that, in selecting the works she has included in “The Meeting Place of Unveiled Worlds,” she had no particular thematic agenda in mind. Instead, she said, she wanted to share with Japanese viewers a range of works by contemporary and historical, British self-taught artists, and to allow each exhibited artist’s work to find its lines of connection to and dialogue with the works around it.

At the same time, she hinted, visitors to the exhibition who might be more familiar with the phenomenon of self-taught artists’ works primarily with regard to what is known as “Japanese art brut” may broaden and deepen their understanding of this field through this introduction to a wide-ranging selection of artworks from another island nation located far across the seas.